By Russel Barsh and Madrona Murphy

Special to the Weekly

Centuries before the Growth Management Act, Lopez Island hosted year-round settlements with a population roughly the same as today. They did not speak English, of course, but Lkungenung, the Coast Salish language shared by the people we call Saanich, Songhees, Samish and Lummi today.

Lkungenung-speaking people lived in at least three large plank-house villages on Lopez, each with a scattering of outlying houses, gardens, reef-net sites, and clam-drying beaches within a mile or so of the core settlement. Based on the size of villages visited by early explorers, this would have represented a total population of 1,800 or more.

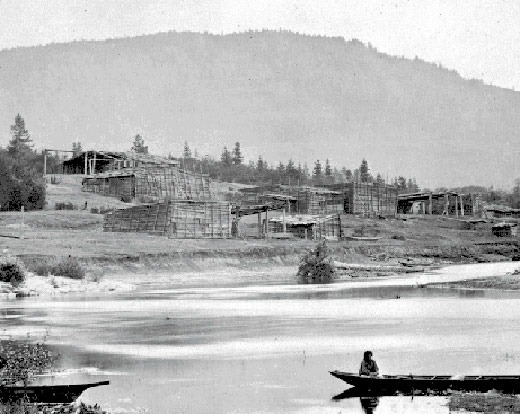

Houses in the core settlements were constructed of cedar-trunk posts and beams, with walls and roofs of split cedar boards tied to the frame. Inside, the floor was divided into dozens of family apartments by low walls of woven cattail mats, looking something like the cubicles of a present-day office building; while the rafters supported attic storage space for dried food wrapped in cedar bark paper, blankets and other textiles.

In the spring when camas bloomed and salmon began their homeward migrations, households in each village dispersed to production sites, mainly within line-of-site of the main village as a matter of security, and within an hour or two by sailing canoe.

The remains of the oldest village on Lopez are located near Richardson. Exposed cultural materials represent at least 7,000 years of human activity, from the seasonal big-mammal hunting camps of the earliest post-glacial visitors, to a year-round plank-house village established about the same time as the Roman Republic in Europe. Outlying reef-nets, duck nets, shellfish beds and camas gardens extended from Cattle Point on San Juan Island to McKaye Harbor, and around the south end of Lopez. Descendants of the high-status families that lived at Richardson are now enrolled as Samish, Swinomish, Saanich (on Vancouver Island) and elsewhere in the central Salish Sea.

A related complex of villages and production sites was located in Lopez Sound, with the largest group of houses at Mud Bay, outlying houses at Hunter Bay and Sperry, and production sites including camas gardens and shellfish beds extending to Swifts Bay and Shoal Bay, where burnt-over gardens were observed by naturalist C.B.R. Kennerly in the 1850s. The plank-house at Mud Bay was at least 800 feet long, judging from the 1951 state archaeological survey of the site. The house or houses at Swift’s Bay left 700 feet of shell middens.

On the west side of Lopez, the core village was at Flat Point, with outlying houses and production centers at Fisherman Bay Spit, and probably also the south-facing bays on Shaw Island. Old-timers told Wayne Suttles that the name of this village was Wulálemus (“facing each other”) because the houses were built on the beaches with the marsh in the middle between them. Settlers ploughed much of the archaeological site, and removed the burials in the 1930s. Nonetheless, the 1951 state archaeological survey found 600 feet of middens and house remains along the waterfront. The leading families of this village live today mainly at Lummi, although they are also related to Samish and Saanich families.

Reconstructing the geography of pre-Contact Lkungenung Lopez draws on public archaeological surveys conducted in the 1950s through the 1980s; extensive interviews with Coast Salish elders by Blakeley-born anthropologist and linguist Wayne Suttles in the 1930s to his death in 2005; and field studies of exposed middens, soil profiles and relic earthworks by Kwiaht researchers over the last decade.

Learn more about Lkungenung-era Lopez, and contemporary efforts to revive the cultivation of camas as a local food resource at www.kwiaht.org.