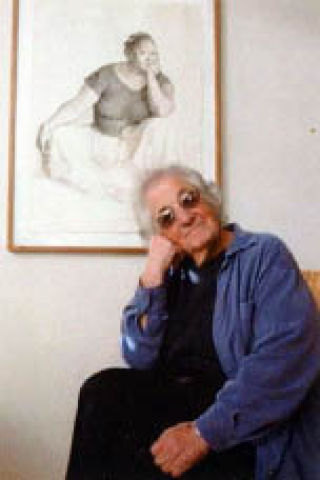

Barbara at home on Lopez Island.

Born in 1931, Barbara lived in Philadelphia with her working class parents and younger sister. First generation Americans with roots in the Ukraine, neither parent had a college education. Barbara’s mother, a talented musician, was a social worker for refugees from Europe. Her father worked in the garment industry and expanded his sixth grade education by attending extension classes.

“I was a big city girl until arriving on Lopez Island ten years ago. I do like being here,” admits Barbara Brownstein.

Barbara benefited from teacher mentors beginning with a chemistry teacher in her public high school. She received a full tuition scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania.

When she entered the University in 1948, all females were enrolled in the College for Women. Her classes had all women students except chemistry and calculus which lacked female enrollment. She married a young veteran student, just back from the Pacific. “That was the way you left home at that time.” Her husband suffered emotional stress from the war and left in 1955. “I was then 23 with two years of college, had held lots of crazy jobs, had two children and was divorced. I needed to go back to school.” Family support and another mentor eased the way. She graduated with a biology degree in 1956. Barbara received a Public Health Service research fellowship and obtained her doctorate in 1963.

A fellowship from the National Institutes of Health allowed her to work in Stockholm at the Karolinska Institute. While there, Barbara worked in virology and microbial genetics when antibiotic resistant bacteria first became evident. Sweden provided childcare while she worked at the laboratories. During those three years, they traveled throughout Europe. When President Kennedy was assassinated, kindnesses were extended to her by the Swedish people.

Her mother’s terminal illness brought Barbara back home where she became a research associate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wistar Institute. There were still few women in the sciences. Barbara joined the Association for Women in Science to obtain equal recognition and opportunities for women. She gave a research seminar on her work as part of a regular faculty application at Temple University without result. “I heard later that the department chair said, ‘This is exactly what we need, now find me a man like Brownstein.’ I accepted an Associate Professorship a year later.” She published research papers and presented at national and regional meetings, remaining at Temple from 1969 until 1995. “I developed a real interest in the teaching and learning of science and the impact of teaching on students.”

With her children grown, Barbara took advantage of other opportunities. A sabbatical at the Imperial Cancer Research Laboratory in London was “a kick with more traveling, learning many more new things and doing research.” After Nixon’s visit, she was invited by the Chinese Academy of Science to help set up China’s first university laboratories in molecular biology.

With impeccable credentials, she was well received by the faculty of Temple University. At sixty, Barbara left administration and returned to teaching biology and developing science courses. An appointment with the National Science Foundation led to work on the transition between Presidents George H. W. Bush’s and Clinton’s administrations. When Temple opened international campuses, Barbara traveled frequently to Tokyo and Rome.

Offering to volunteer at the Lopez School where she thought she might do some workshops, Barbara was promptly elected to the school board where she served one term. Locally, she has found satisfaction working with the Domestic Violence Sexual Assault organization. Aware that domestic violence cuts across all social and economic levels, Barbara was surprised to learn about its frequency here. Teaching genetics classes through Skagit Valley College has encouraged her to create a lecture series for the local community.

Disappointed at the contentiousness of the education reform movement, Barbara doesn’t “regret doing what I did but I don’t see a lot of results except in individual cases. Good people burn themselves out. It’s hard to change things.”