by Yuki Wilmerding, Susan Ridl, Anna Campbell, and Kai Hoffman-Krull

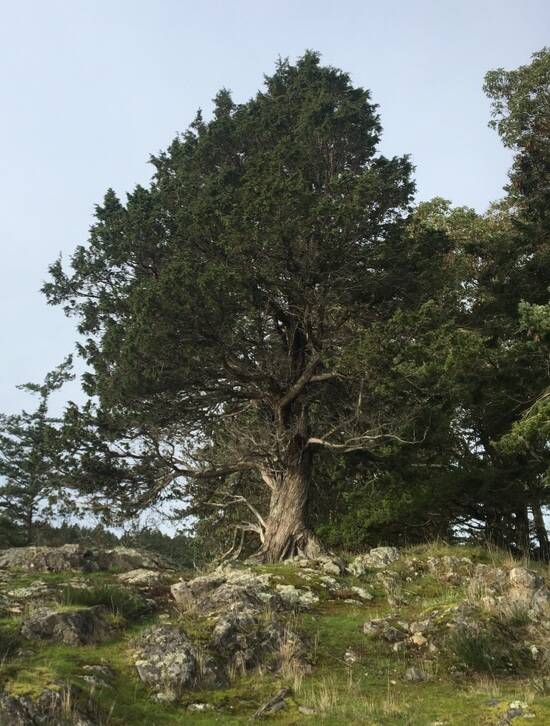

Juniperus maritima, or Seaside Juniper, is a recently uncovered species of juniper that fringes our shorelines, hanging off scraggly outcroppings and jutting from rocky ledges on the coasts around the San Juan Islands. Also known as Maritime juniper, this native species may also be a resilient and long lasting part of our archipelago ecology in a changing climate. Like many other juniper species, Seaside Juniper can grow in most challenging conditions except for one key need: sunlight. The trees are often found in areas that are uninhabitable by other species, such as rocky, storm-swept beaches, rocky balds, and bays. This is in part because the Maritime juniper is also one of the only coastal conifers that are tolerant of salt spray from the ocean.

This preference for harsh terrain, being both windswept and lacking in rich and sufficient soil, means that even the smallest of Seaside juniper have, more likely than not, already exceeded your lifespan. Up until 2007, the Seaside juniper was thought to be a Rocky Mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum), but genetics showed it was a distinct subspecies. In regards to geographic distribution, the Rocky Mountain juniper is found in higher and drier environments, while Seaside juniper is endemic only to the Northwestern Washington state region to Southern British Columbia, where it is lower in elevation and wetter. Other distinctions that were made were between the morphology of the different species was that Seaside juniper have quicker maturing cones.

Within the Salish Sea basin there is a lack of birds that are known to feed on Seaside juniper cones, another factor limiting seed dispersal and migration. This results in populations of this unique juniper having a very narrow range, constrained within the islands they currently reside. In Coast Salish culture juniper had spiritual and protective properties, and the boughs were used to protect and prevent illness and disease (Turner and Hebda, 2012). The wood of the Rocky Mountain juniper was used by the indigenous peoples of the interior for a variety of uses.

As the junipers grow older their form fills out into a bushy conical shape. They prefer to go in open areas away from other trees, which is one of the reasons they are found in the nearshore habitat where Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) encroachment does not crowd them out. Fire scars on Cedar Rock Preserve on Shaw Island, and many other preserves in the San Juan Islands, are evidence of past prescribed burns, indicating a managed woodland that once likely had Seaside juniper in the interior. Due to the current growth of forests during the age of nationally legislated fire suppression, these open woodlands are now much denser, closed forests that are not suitable for Seaside juniper. The junipers that can be found along the forest edge or interior show loss of foliage, discoloration of needles, and stunted growth.

The ones growing along exposed shorelines are also not safe from peril however, as coastal erosion destabilizes their roots, causing them to gravitate onto the beaches below. This creates value to the beach however, as large woody debris contributes to shading pebbly substrate where spawning fish can lay their eggs.

There is limited research available about this remarkable species of juniper but they are resilient species that ecologists predict will persist throughout our changing climate, due to its resilience in harsh environments. Currently, however, the Seaside juniper is listed as vulnerable by the Nature Conservancy due to its low recruitment, threats from human development and Douglas fir encroachment, and its exposure to storms. If you live near the shoreline, or simply have open space with sunlight, consider planting a Seaside juniper. You will be helping a part of our past to become our future.