This is the second story in a two-part series about the effects of climate change on San Juan County.

Changes in sea-level rise are causing San Juan County staff, like many coastal municipalities, to re-examine how to ensure the sustainability of public roads.

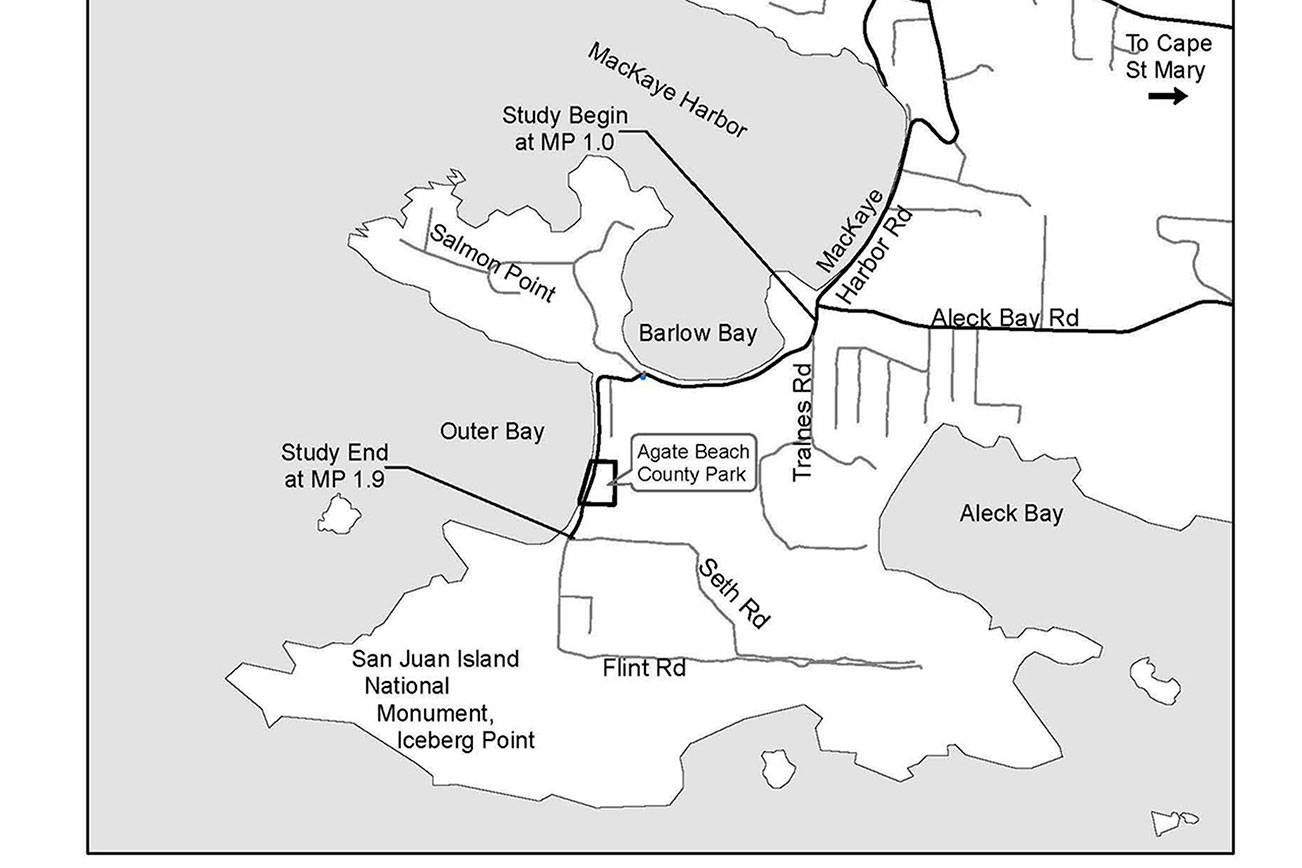

This can be seen in the county’s plan for MacKaye Harbor Road on Lopez Island. The short-term goal is to move part of the road in front of Agate Beach County Park inland by 2021 to protect it from erosion. The long-term plan is to potentially place about a mile of the road’s southern end inland, as well as to a higher elevation, to protect it from sea-level rise projections.

Shannon Wilbur, the senior project engineer at San Juan County Public Works, said she believes this is the first time county staff has evaluated moving a road based on projected sea level rise caused by climate change.

Erosion

Since Dean Anderson moved into his home off of Mackaye Harbor Road in 1978, part of the county street has been relocated due to erosion, and plans to move another section will start this year.

Last spring, part of MacKaye Harbor Road along Agate Beach County Park was reduced to one lane as erosion eats away at the bluff and the road on top of it.

“It’s annoying,” said Anderson. “In general, I think something needs to be done.”

MacKaye Harbor Road is roughly two miles long and located on the southwest end of Lopez Island. Waves accelerated by wind hit sections of the bluff, which the road is on, causing the southern end to erode.

Parts of the road are so close to the coast that they fall under the definition of shoreline, said Wilbur. This includes property located 200 feet from the area’s average highest water line. This year, county staff will start plans to move the section in front of Agate Beach County Park inland, which is projected to cost $955,000. Funding sources, like grants, have not been secured yet.

Aabout 20 years ago, another section of MacKaye Harbor Road, located south of the park, was also visibly eroding, said Wilbur. In 1992, county staff moved the section inland, roughly 30 feet at its highest point, securing access to area homes.

“If the road had not been moved, it would be down on the beach by now,” she said. “Any properties back [at] the end of MacKaye Harbor Road, such as Seth Road or Flint Road, would not have been able to get there if the road had failed.”

Cattle Point Road on San Juan Island was also relocated due to erosion in 2015. The project had first been discussed a decade prior.

Sea-level rise

Today, county staff are looking at more than the effects of erosion when evaluating the maintainance of coastal public roads.

“We are starting to see more impact from sea level rise now in low-lying areas,” said Wilbur. “It’s becoming more apparent during storm surges.”

According to the MacKaye Harbor Road Feasibility Study, the road’s lowest elevation is near Barlow Bay at 11 feet. A 2017 photo shows sea spray reaching the road during a wind storm, “although it was not an exceptionally high tide,” states the report.

The feasibility study looks at potentially moving the part of the southern end of the road, starting near Aleck Bay Road, past Barlow and Outer Bays and Agate Beach County Park, to Seth Road. This section is the only route to Anderson’s property as well as about 80 other houses, tribal land, the county park and a national monument.

However, San Juan County Council Chairman Rick Hughes said the potential move of the road’s southern end cannot begin until county policy issues are addressed. Questions have risen like whether county staff has to provide access to areas with rising sea levels and if they are accountable for the loss of property values.

“Do we keep fixing the road or create a path to have … for the next 70 years?” asked Hughes. “We don’t have answers yet.”

Around MacKaye Harbor Road’s lowest point, near Barlow Bay, the average highest water height is 7 feet. Based on the project’s designated sea-level rise projections, this average will be around 12 feet in 100 years. The authors of the feasibility report increased the feet to account for storm surges and decided to place the road to a roughly 20-foot elevation line.

The feasibility study uses predictions from the Intergovernmental Plan on Climate Change to designate sea level rise projections at the center’s high levels of 1.57 feet by 2050 and 4.69 by 2100. IPCC is comprised of hundreds of scientists, across the globe, and was partly founded by the United Nations.

The project’s study notes a 2017 report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration which attributes higher sea levels to increases in flooding. In 2013, the local environmental nonprofit, Friends of the San Juans, also reported that inundation and erosion increase as sea levels rise, which is accelerated by climate change.

The MacKaye Harbor Road feasibility report estimates it would cost $3.1 million to relocate the southern end inland and to a higher elevation. The report stated a second $10.8 million option to raise the road until erosion and sea-level rise forces the road to be moved and then relocate it.

To Mike Bergstrom, that seems to be a lot of money for a projected problem. Bergstrom is with MacKaye Harbor Inn, located north of the southern part of the road that the county may relocate.

“Predictions are just that,” he said. “Take a look at the sea level rises for the past 50 years. Water has never been close to MacKaye Harbor Road.”

Sea level in Friday Harbor has risen 0.38 feet in the last 100 years according to NOAA, while the project leaders are estimating a roughly 5-foot rise in the next century.

Clifford F. Mass, a weather blogger and professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington, attributes the increase in sea-level rise to the release of carbon dioxide.

According to NOAA, CO2 is mainly released during the burning of fossil fuels, like coal, and helps to trap heat on Earth instead of releasing it into the atmosphere.

Paul Kamin, the general manager of Eastsound Water Users Association, said Crescent Beach Drive on Orcas Island also has the potential to be underwater one day. Kamin has photos of the road with driftwood from the beach covering the street after a March 2016 storm. Wilbur noted that when the road on Crescent Beach is out, there is another street homeowners can use to access properties while there isn’t one for the southern end of MacKaye Harbor Road.

Wilbur said no other public roads are currently scheduled to be reviewed for relocation due to erosion or flooding, though there are 20 miles of public roads located within 200 feet of county shorelines.

Utilities

When the county moves a public road, Wilbur explained, utility companies are not mandated to relocate their lines as well – though they often do. Kamin said it is most cost-effective if the county and utility companies work together. He explained that Eastsound Water has to replace the water main along Crescent Beach Drive soon, whether the county moves the road or not, because the pipe is over the age of the national standard for water mains.

“It would be irresponsible for Eastsound Water to install a new pipe with a life expectancy of at least 75 years along the existing roadway,” he said. “A water main submerged in seawater is a bad idea.”

There are water and power lines along MacKaye Harbor Road as well, according to the feasibility study. The report states that the water main along Agate Beach is in “poor condition.” Another water main north of the area broke a few years ago, states the report, and the break showed how vulnerable the line is since it’s so close to the shoreline.

Dan Vekved with Orcas Power and Light Cooperative said there are plans to move part of its line along MacKaye Harbor Road underground and would welcome the chance to work with the county on it.

While county employees focus on the MacKaye Harbor Road relocation on its southern end, just about a mile north, the part of the road that runs past Jan Johnson’s property has never been moved. He said there aren’t any signs of erosion or flooding, either. Johnson, who has owned his home since 1965, isn’t worried about changes he doesn’t see now and maybe never will.

“From what I’ve read, water might come up in 100 years but I’ll be long gone by then,” he said.

Read the project’s complete feasibility study at islandsweekly.com.