Nearly a decade after the southern resident killer whales were listed as endangered under federal law, the U.S. Fisheries Service is now proposing to give Lolita – the orca captured 44 years ago in Penn Cove and sold to a Florida aquarium – protection of the Endangered Species Act as well.

On Jan. 16, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration backpedaled from its previous stance and recommended that Lolita, also known as Tokitae, be included along with her southern resident cousins on the ESA. The agency will accept public comment on the proposal until March 28 and then begin a months-long exploration as to what type of protection such a designation would afford to the captive killer whale.

But if you think that means Lolita will be released and reintroduced to the waters off Washington, don’t hold your breath. That might take awhile, if ever.

Lynne Barre, branch chief for protected resources at the National Marine Fisheries Service, said Lolita’s proposed listing under the ESA includes language in which reintroducing the orca into the wild could be considered a “take,” creating potential harm to the animal, which in itself would be a violation of the ESA. Still, she said that the agency will consider comments about a possible relocation as part of its upcoming evaluation. Barre noted that other animals afforded protection under the ESA remain in captivity for various reasons, as part of breeding programs, because of injuries or because they have never been acclimated to the wild.

She said the Fisheries Service is collaborating with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which is faced with a similar dilemma following its proposal last year to list chimpanzees under the ESA because of a history with captivity.

“We’ll be collaborating with our colleagues at Fish and Wildlife about how the ESA applies to captive animals,” she said. “Because of the similarities we may look to each other for guidance.”

Barre said that although the Endangered Species Act has been in effect now for 40 years, circumstances arise, such as management and treatment of captive ESA animals, where there’s uncertainty about what the interpretation of that law means.

Declared endangered by the U.S. in 2005, the southern residents consist of three closely related clans, J, K, and L pods, which make the waterways of the San Juan Islands a seasonal home. The population, believed to have been historically in the hundreds, plummeted to 71 by 1973 following the captures for marine parks, which ended in the 1970s. It rebounded to 80 in 2002, and has hovered in the mid-eighties since that time. The southern residents are also considered endangered in Canada.

Scientists believe a prolonged decline of the killer whales’ preferred prey, Chinook salmon, disturbance from vessels, and pollution are the leading threats to the population’s survival.

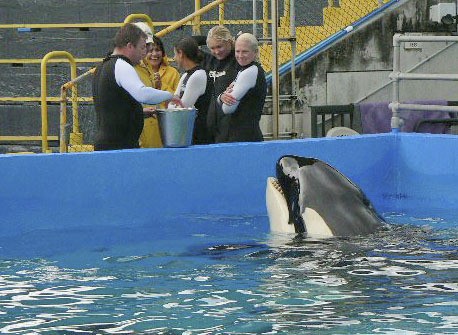

Lolita is the only survivor of 45 southern resident orcas once held in captivity. She is believed to have been about six years old when she was captured in 1970, along with six other southern resident whales, and has lived her entire life in a pool at Seaquarium in Miami, Fla. Lolita has not had the companionship of another killer whale for more than 30 years, since her pool mate, Hugo, died in 1980 after repeatedly slamming his head against the side of the pool he shared with Lolita for two years.

Orca advocates, along with several prominent animal rights groups, have sued the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees living conditions of animals held in captivity. In addition to being denied companionship, the lawsuit argues that the tank in which Lolita is held is too small for its size. Miami Seaquarium maintains the whale’s living conditions comply with or exceed the Department of Agriculture’s regulations.